Cultural influences

Geert Hofstede, a Dutch social psychologist researching cultures, defined culture as “a collective programming of the mind that distinguishes one group or category of people from another”.

In our modern cultures, probably in every country, we have an unhealthy relationship with anger. We’ve been trained to demonise it; hence, it manifests in extreme forms: we either reject and deny it or/and, after we’ve done it for such a long time, we then explode, blow up like a volcano. An attempt to avoid and disconnect from this emotion (or any other emotion) will backfire on us and others at some point.

Some groups, for example, women or black people, have less “social licence” to express anger as they will get negatively labelled or ostracised by society. Paradoxically, it’s more acceptable for men to display anger or aggression as a sign of strength; however, it comes with some side effects. Men are expected to hide, often under anger, all other “unacceptable” by society emotions – fear, sorrow, vulnerability, uncertainty – otherwise they will get labelled as weak, not masculine enough. I was rewatching recently one of Carl Rogers’ therapy recordings from 60s in the USA, where one of his black male clients admits:

“Maybe if I become angry and I really let it hang out, then I really would see how hurt I am … to really show that … how can I trust that to somebody?”

Showing anger can be a vulnerable place, because our society struggles to accept it.

I’ve been wondering how anger tends to be expressed in different cultures. Matsumoto and his colleagues (Matsumoto et al., 2010) studied the expression of anger across cultures in 32 countries:

“Individualistic cultures were associated with greater endorsement of angry expressions toward ingroups compared to outgroups; collectivistic cultures, however, were associated with greater endorsement of angry expressions toward outgroups than ingroups.”.

By “ingroups” they mean familiar and intimate relationships; by “outgroups,” they mean strangers.

It seems like in authoritarian and collectivistic cultures, workplaces and families, anger is used by authorities to control their subordinates and maintain power. Of course, those at the bottom of the hierarchy – children, employees, juniors – cannot question back; they are expected to obey. Slavoj Žižek makes a good comparison between authoritarian and post-modern societies. He is a Slovenian philosopher whom I appreciate for his raw, imperfect personality we can see during his talks. He notices that in the authoritarian system with a brutal boss, “we still retain our internal freedom, we can rebel”, and be furious at them. On the other hand, in the western “post-modern non-authoritarian permissive” culture, we have the apparent freedom and permission to be authentic, but is it a real freedom or an illusion? He continues: “Beneath the appearance of a free choice, it gives you a much harder choice and… it’s almost impolite to protest”. In the West, we have created this polished, sterilised society that looks equal and polite on the surface, but it’s often false and fake, at the price of “oppressed, controlled” anger. You can watch Žižek’s examples in this short video and here too.

Of course, none of these models are ideal or healthy, but I’m exposing here the hypocrisy, the manipulation, and allure of so-called freedom that could be more perversive and deceptive than an obvious lack of freedom.

“Here in America, people try hard to cover up the daimonic. But obviously, it is much more damaging covered up than it is out in the open.” (Rollo May)

Here is why: when someone is openly angry at me, at least I know where I stand, the cards are open, I can address it or defend myself. However, with superficial mannerisms and potential passive aggression, I don’t really know what the other person thinks, and it leaves me in this ambiguous space: I can sense they’re not happy with me, but when I only pay attention to their words, everything seems to be fine. So, I feel gaslighted, and I start to question myself whether I am imagining stuff. It does not feel genuine to me. Most of the time, I prefer the worst painful truth to a pleasant lie.

Therapy space

Working as a psychotherapist in the West, I noticed that even my clients are apologetic about their anger and struggle to express it openly in our sessions. Despite my invitation and encouragement to do so, they feel guilty and uncomfortable doing that. One of the purposes of therapy is to release our emotions and to be as real and free as possible, so if clients hold their anger back, then where else is it safe enough to let it out? If we turn even therapy rooms into a sterilised place, where clients use self-censorship and try to please their therapist rather than pleasing themselves, then we are dealing with a real societal issue.

“The alarming rise in postmodern psychopathology is directly related to the denial of the diamonic, and particularly to the chronic dissociation or repression of anger” (Stephen A. Daimond)

Political correctness in the West has been transmitted into the therapy arena, even amongst mental health practitioners. It is a failure of therapy and the therapist if they further repress the daimonic rather than welcoming the client’s raw emotions and judgmental parts to facilitate catharsis. So, another question arises: how many therapists and mental health practitioners have truly confronted their own rage and therefore can sit comfortably with the client’s exasperation? And if not, can we expect clients to even consider showing their fury if they pick up on the therapist’s apprehension?

“The task of the therapy is to conjure up the devils rather than put them to sleep” (Rollo May)

In the mental health, psychology, and coaching world, I come across courses titled “Anger Management”. That word “management” implies as if it is an object that just needs to be sorted, polished, and put in the right place, and everyone will be happy ever after. It’s a false assumption of our society’s increased need to measure, control, and rationalise every aspect of our lives, which is a domain of the left hemisphere. Iain McGilchrist, a neuroscience researcher, outlines the differences between the brain hemispheres in his “crude soundbite: The right hemisphere helps us to understand the world, the left only to manipulate it … emotional and social intelligence, no surprise, is more associated with right hemisphere function”.

Sanity vs. madness?

“The neurotic is not merely someone who failed to adjust to the world, but a potentially superior individual who fails at being creative” (E. James Lieberman, psychiatrist)

What makes us think that (only) people who are well-collected, well-mannered, composed, polite, and not showing visible signs of distress or agitation are truly the mature or noble ones? In many social situations, jobs, and settings, our society values one’s emotional stability more than their degree of wisdom, authenticity, or humanity. Saying, “I’m angry”, showing our sincere, raw emotions is not perceived well in most cultures. It can be equated with madness and insanity. Our societies created this notion of avoiding unpleasant feelings, especially anger. Perhaps we should revisit and question these social constructs. What we perceive today as normal and common doesn’t necessarily mean it is healthy and conducive.

“I do not believe in toning down the daimonic. This gives a false sense of comfort.” (Rollo May)

Many people wish to skip anger and remove it from their lives. People often say, “But I don’t want to feel angry. I want to control it”. How can we control something if we don’t understand its origin and complexities? Also, what is wrong with anger? Anger is just one of the human emotions that we are meant to feel. It’s like saying: “I don’t want to feel physical pain when I get hurt, it’s unpleasant”. Hell yeah, it is! But how can we protect ourselves, stop further harm, look after the wound, and let it recover if we get rid of the pain sensation?

Can you resonate with any of the descriptions above? What is the attitude towards anger in your family, community, and country? Do you feel there is any space for healthy anger to be expressed in your close circles?

Personality types

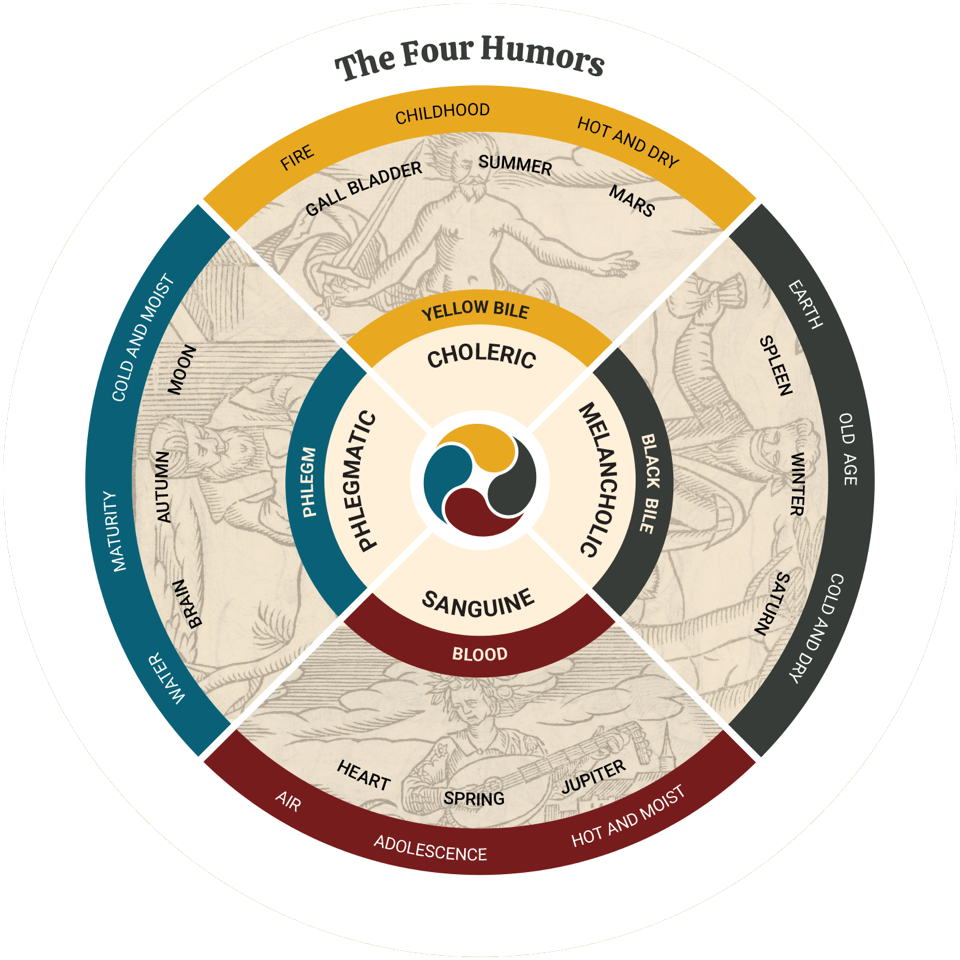

Apart from the family messages and cultural influences, our temperament and personality type can determine the intensity and frequency of our irritability. Hippocrates came up with a concept of four types of temperaments, named after bodily fluids: Choleric, Melancholic, Phlegmatic, and Sanguine. Phlegmatic and sanguine types have a more relaxed, equable, and tolerant approach to their reality, so anger might not be their regular or primary felt emotion. On the other hand, Choleric types are more prone to frustration and impatience. The word “choleric”, translated from Old French colere “bile, anger”, means “easily angered, hot-tempered”. Hippocrates connected this temperament type with the yellow bile. In TCM (Traditional Chinese Medicine), anger is represented in the body by the liver organ, which produces yellow bile. This theory is fascinating in terms of the link between our emotions and physiology.

For example, an American writer Fran Lebowitz is unapologetic about her character type:

“I am a very angry person. I am angry almost all the time, especially when I’m not alone. I know my anger is disproportionate, and I don’t express it. I knew from a really young age: do not act on this.”

Maybe her anger is one of the reasons that makes her a great writer and a nonconformist.

Another personality theory developed by Meyer Friedman and Ray Roseman talks about contrasting type A and type B. Type A is described as more competitive, aggressive, impatient, and ambitious, with a sense of urgency. Where type B is characterised as more patient, flexible, and easy-going. Type B is often conflict-averse, so their anger will not be up in the open.

We need all however many types of personalities there exist, for a healthy, diverse society, because each of them serves different roles and purposes.

In part 3, I will explore how powerful anger can be in establishing our core essence and what’s the difference between being nice vs. kind.