The taboo of anger

“You look angry” – “No, I’m not angry!”, replies with an angry voice.

On the other hand, anytime we hear someone telling us: “Calm down”, we get even more agitated, don’t we? 😉

In our society, we don’t like to admit that we feel angry. We think it’s some form of weakness, a flaw, a plague to be avoided, or a sign of immaturity. We are afraid of it. I hear over and over again how people try to feel less angry. But why? I get it, being angry might not be a comfortable state. But if we were only seeking pleasant feelings, we wouldn’t go very far, would we? We wouldn’t even be here, as giving birth is extremely uncomfortable. Fortunately, I have good news: anger is not a problem in itself. Anger is like a sharp knife; it’s a tool that can be used to destruct or construct. It can be a necessary daily object to serve our needs, for instance, to cut our vegetables or to create a stunning artwork. Or it could be used as a violent device to hurt others (or ourselves) and cause pain. Thus, it’s all down to the user, but the knife itself is neither good nor bad. The same with anger, and any other emotion, it serves a purpose, and it’s down to our decision what we do with it.

It’s important to differentiate anger, an emotion, from aggression, abuse, and violence – an act, a behaviour. Anger can become scary, destructive, and violent if we don’t understand it. We can feel angry, but it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to turn automatically into aggression. Moreover, we could perform our aggression towards objects, which is still not abusive towards a person. But what’s more poignant aggression is often a result of unresolved and not properly addressed anger in the first place.

I am in line with Stephen A. Diamond’s preface to his book: Anger, Madness, and the Diamonic: The Psychological Genesis of Violence, Evil, and Creativity:

“Any civilized society and any so-called religious or spiritual movement must frankly confront the thorny paradox of anger or rage, and that refusal to do so contributes to and perpetuates the epidemic evil, violence, and madness tearing us apart today”.

What is our relationship with anger? What affects our views and attitudes? Are we aware of what makes us afraid or uncomfortable around it? What do people mean when they wish to “control” their anger? What’s the correlation between anger, depression, trauma, freedom, creativity, and evil? How to differentiate our destructive anger from the constructive one?

I divided this essay into 7 parts to make it easier to digest, so you can jump to the end, where I discuss how to embrace anger, or skip to a specific section that interests you.

- Part 2: Culture and personality types

- part 3: Anger as personal power

- Part 4: Anger vs. trauma, depression. What anger has to do with freedom and choice?

- Part 5: Unmet needs. How anger is part of our creativity?

- part 6: Anger necessary for progress

- Part 7: Courage to embrace anger

Why am I writing about anger?

One of the main reasons why I’m approaching this subject so passionately is my search for truth and authenticity. First and foremost, the internal truth. I think, anytime we deny, disown, or suppress our unpleasant emotions, it might be jealousy, envy, anger, rage, revenge, despair, fear, vulnerability, it is deceiving ourselves, seeking illusion, rationalising our emotions, and not living in reality. It takes courage to look inside and face our anger, because it can be scary and requires some level of honesty with ourselves.

We need courage to “begin to engage in the frightening task of exploring the turbulent and sometimes violent feelings within [us]”. (Carl Rogers)

The second reason is I noticed that anger is probably the most misunderstood emotion. We made it taboo in our societies, next to subjects like money, death, religion, sex, mental health, and loneliness. I want to un-taboo anger. I love anger! It’s more positive than negative for me. I’m very thankful for it as it directs and empowers me to live faithfully to my values and constantly improve myself.

My aim here is to demystify, raise our self-awareness, and increase our understanding of this emotion. We must revisit the cultural norms and beliefs and embrace all the advantages of anger. I want to advocate for a healthy and constructive anger, because it’s our personal power. This will not only make us more informed experts in making sense of our emotions, but it will enhance relationships with our families, communities, and as citizens. I’m not promoting a wild and uncontrollable expression of rage, but rather I am hoping to initiate honest, open dialogues and discussions with the “spirit of civility and mutual respect” (Michael Sandel, philosopher).

How do we define anger?

Emotions and the definition of anger

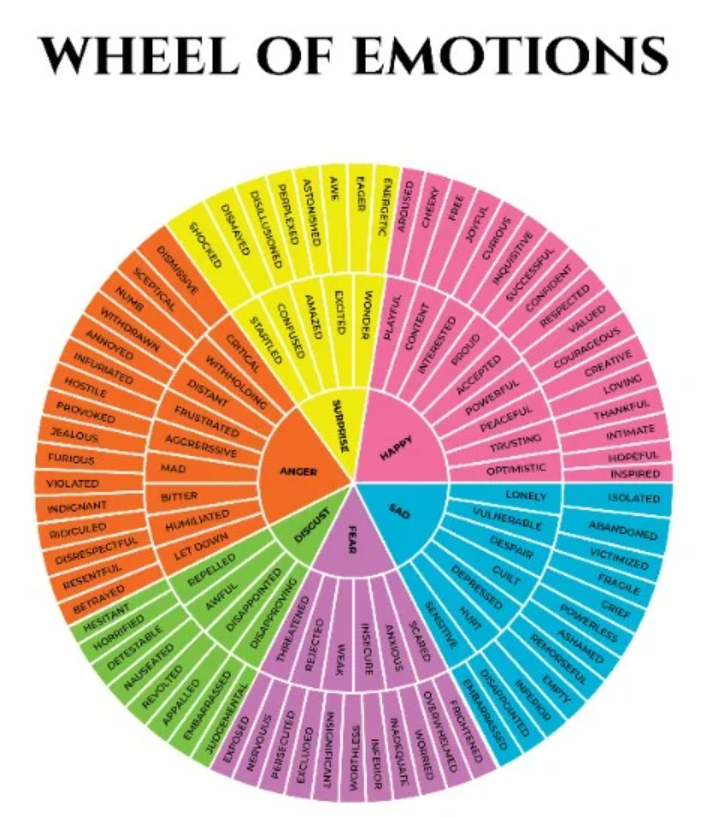

Let’s start from the basics, from the etymology of the word “anger”. Angr in Old Norse is translated as “distress, grief, sorrow, affliction”, also from Old English enge meaning “narrow, painful”. Interestingly, the word “angst” and “anguish” has the same root as “anger”. I’m curious about the etymology of anger in other languages. It shows up in all gradations; from frustration, irritation, annoyance, agitation, jealousy, exasperation, resentment, embitterment, discontent, irascibility, ire, indignation, to madness, rage, fury, and wrath, to name a few.

According to psychologist Paul Ekman, anger is one of the six basic emotions, alongside happiness, sadness, fear, surprise, and disgust.

Let’s go deeper: what are emotions? The word “emotion” comes from the Latin word emovere, which means to “move, move out, remove, agitate”. This definition is important in understanding the role of anger, which I will discuss throughout this essay, because emotions serve as a motivator, a drive, they mobilise us, move us to meet our needs. For instance, dance is emotion in motion. Emotions have a purpose; they are messengers, a GPS signal showing us directions. As I learned many years ago from my Polish mentor, Mieczysław Wojciechowski, emotions are not the actual issue; similarly, the signal of a fire alarm or smoke detector is not a problem, but rather an indicator of a problem – the fire, in this case. Therefore, demonising anger (or any emotion) is as fruitless or even dangerous as trying to control, suppress or fight the fire alarm for making a loud noise, instead of dealing with the real issue – addressing the fire, i.e,. our situation.

In addition, neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp, through his studies, distinguished seven primary affective brain systems that we share with other mammals. They include (he capitalised them) CARE, LUST, SEEKING, PLAY, PANIC/GRIEF, FEAR, and RAGE. They’re all necessary for our survival and thriving. Panksepp explains that “basic emotions emerge from deep, ancient brain structures, including the amygdala and the hypothalamus”. But they don’t only happen in the brain, emotions show up in our bodies too: “We can’t separate the emotions from the physiology” (Dr Gabor Mate). Neither should we separate emotions from reason. Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio’s research and other brain studies show that we make better decisions when our emotions are involved.

Clearly, we all experience anger, but where is it going if we rarely acknowledge and talk about it? When we try to suppress or numb our anger, it is as if we deny 1/6 or 1/7 of our humanness, of our essence, our core. Anger is part of our nature; it is experienced universally across all cultures. Even when we stifle it, it’s still there, it’s not disappearing, just finding other ways to manifest, to act out, and this is where it gets out of hand. When we don’t understand it, it will control us.

As my mentor says, our anger, most of all, is a clue and indication for us (rather than for others). So, I will focus here on the internal experiences of anger. As I believe, once we master our own frustrations, once we dissect and become more comfortable with this emotion, we will be able to learn how to navigate it in the external world in relationships with others.

In this essay, I am inquiring anger’s various aspects and angles. Here, I’m including all my ponderings, relevant reflections, and findings, and presenting opinions of other experts and thinkers. Of course, my views are limited by my veil of ignorance and never-ending personal blind spots and biases; therefore, my notes are incomplete, can’t be final, fixed, or dogmatic. I keep learning and discovering each day, so I trust you, Dear Reader, that you will apply, to quote the scientist Carl Sagan, the delicate “essential” balance between your openness and your critical thinking and scepticism to ideas presented here.

In the first and second part, I’m going to look at how our families, religion, spirituality, culture, and societies shape and distort our beliefs about anger. Additionally, I will explore how our personality type can determine our approach to it.

Growing up

If we want to understand anger, we should observe babies. They show it instinctively from the first moment they’re born, through crying, scratching, pulling, fussing, and facial expressions. They do it unapologetically to communicate their needs and wants. Therefore, anger is a fantastic survival strategy. But very soon, young children become conditioned and socialised by most adults around them. Many of us were punished or shamed for feeling and showing anger, so it became taboo in most families and schools. No one taught us to be okay with it.

Growing up, we witness and experience an ugly expression of anger in our families, whether it’s abuse, violence, fights, screaming, or the opposite extreme – an atmosphere of silent searing, passive rage. This is scary and highly unsettling for children. No wonder that we start to associate anger with being hurt or hurting others. Sadly, we rarely see any resolution of fights, that our parents could make up and things would be alright again.

As my clinical supervisor and psychotherapist, Pauline Gordon, explains, approaching the subject from an attachment-based theory: “We become ashamed and embarrassed about the feeling, we don’t want it to be seen, because people might walk away from us, they won’t want us. We’re frightened of rejection because of anger: You won’t like me anymore. It’s hard to trust that I’m still lovable, or I will still have my job if I let my anger to be seen”. As kids, we quickly learn that if we show our authentic irritation, then we run a risk of not being tolerated or even being abandoned, and we carry this unconscious belief throughout our adulthood. Fortunately, as adults, we can revisit and review these messages.

Pauline also mentions the notions of “cold rage” and “hot rage”, the Pursuer-Withdrawer dynamic in relationships. The Pursuer shows overt anger and aggression, and we think they’re the troublemaker, where the Withdrawer shuts down, demonstrating it passively – that’s anger too, cold rage, and “it can hurt even more because it’s hard to grasp, it’s silent”.

As children, we learn that anger is risky, because we mainly saw harmful manifestations of it, but nobody taught us how to feel, digest, and express it in an assertive, non-violent way. With all these messages, we develop negative associations with anger, quite understandably. So, what do we do? Many of us decide to completely remove it from our lives. But of course, we cannot. And we should not. It will run our lives secretly, but it won’t go away just by simply ignoring it. In the same way, our rubbish will start to stink if we hide it in the cupboards and pretend we’ve got rid of it. Anger builds up over time and then comes out as an explosion, because we kept pushing it down. We lose our shit, and then we feel guilty and blame ourselves as if we are bad people, which reinforces the false belief as if the anger got us into trouble, so we try to push it down even more. And we end up in this vicious loop.

We can learn about anger from teenagers as well. They get a bad rap for being “difficult” because they stop pleasing others. But adults are the difficult ones, not the children. Teenagers rebel against adults as a way of asserting themselves, setting up their autonomy and independence, wanting to do things their way. It’s a natural developmental stage towards individuation and adulthood. Rather than reprimanding their choices, we should embrace and respect their explorations, of course, within reason, and at the same time offer our compassionate guidance. It all starts from our families: if parents are comfortable with their anger, their kids will observe and learn that anger is Okay.

A healthy and secure dynamic would mean understanding that somebody can be angry with me, but it’s not changing our bond; I am still loved and accepted by them despite me messing up. Equally, if they messed up, I can acknowledge that I am angry, these are my feelings, without making it the other person’s fault (at least not 100%), nor making them responsible for my anger.

Religion & spirituality

Different religions also have their roles in our perception of anger, by preaching that it is a bad, “negative” emotion and that good people mustn’t feel angry. For example, according to the Christianity taught by the Roman Catholic Church, wrath is one of the seven deadly sins, next to pride, greed, envy, lust, gluttony, and sloth. Which by the way is incongruent with the Bible, as the Old Testament’s God itself gets angry and jealous. Also, Jesus in the New Testament shows his righteous outrage by overturning the tables in the Temple, which was a sacred place. Even when we don’t identify ourselves with any specific religion, we were possibly shaped by its teachings and made anger sinful in our hearts and minds.

Spirituality

Over the last few decades, coinciding with the decline of religion, I have noticed how the so called “spirituality” has become increasingly fashionable in the West (for me, the word “spirituality” has become a buzzword and has lost its original meaning). Some people use spirituality as a bypass and coping mechanism for their fears and unresolved traumas, instead of truly addressing them. They aspire to become enlightened and think that experiencing anger shouldn’t be in their repertoire of emotions. They want to become higher, more virtuous beings. This gives them a licence to indulge themselves in their sense of moral superiority, implying: “No, I don’t get angry, I’m always peaceful and full of compassion….” type of approach. I remember during a stand-up comedy in London, one of my favourite comedians, David McSavage, made a joke: “Have you noticed that spiritual people are aggressive?”.

Also, in the mindfulness and meditation communities, there is often a widespread misconception that the goal of meditation practice is to calm the mind, but for some, “calming down” has become another form of control and disconnection. I don’t want to be tranquil and unruffled all the time: “A healthy person cannot be always peaceful” (Mieczysław Wojciechowski). Emotions are not constant; they constantly change. In contrast, being “zen” when the situation requires us to react is a form of compliance and submission. Those who are truly connected to their wrath and unafraid to feel it are the ones who can afford to be peaceful and kind at heart:

“Enlightenment that excludes the daimonic or what Carl Jung called the shadow by touting the transcendental power of our rational “better angels” while denying that of our irrational demons is delusional and doomed to disaster.” (Stephen A. Daimond)

Stoicism

Those who are neither into religion nor spirituality use stoicism as a philosophy to cultivate inner calm and equilibrium regardless of the external events. Of course, being peaceful can be a virtuous thing, but it is an oversimplification of what Stoics meant. Some people interpret stoic as being emotionless, unaffected, and rational. It’s a similar mindset to the religious or spiritual approach I’ve described before: a fantasy to be in control, intellectualise and think their way out of emotions, by suppressing anger.

But why? What is wrong with anger? I want to be affected, moved, and disturbed by the reality because that makes me feel alive, emotionally sober, and actively engaged in my and other people’s lives. Of course, I will constantly strive to be kind, civilised, and more responsive rather than reactive to my agitation. But I don’t want to be a robot, cyborg, or an AI. I’m interested in being a caring, at times fragile human being with my flesh, blood, heart, desires, longings, needs, and insecurities. Even when it’s uncomfortable, painful, and unbearable. I am willing to feel all the range of emotions, from joy, exuberance to anguish and loss. And all degrees of anger.

In the next part, I will discuss how anger is expressed in individualistic vs. collectivistic cultures. I will also look at how our personality types affect the level and frequency of our anger.

[…] This is part 2 of the essay on anger. You can read part 1 here. […]

[…] is part 3 of the essay on anger. You can read part 1 and part 2 to get a full […]